By now you’ve probably heard that pioneering No Wave trio Ut has reformed and will be touring the East Coast in November.

Their mini-tour starts at Brooklyn’s Issue Project Room, where musician David Grubbs and art historian Branden Joseph have organized Theoretical Music: No Wave, New Music, and the New York Art Scene, 1978-1983, a three-day event examining the intersections as well as the failed encounters of art, music, and cinema in downtown Manhattan.

The festival starts on November 3 with a rare screening of James Nares’ No Wave epic, Rome ’78.November 4 features an evening of panel discussions among some of the most notable figures to emerge from the art, music, and film scenes of the time.

The festival concludes on November 5 with a concert performance headlined by the first New York appearance in years by Ut.

Co-organizer David Grubbs was gracious enough to answer a few questions about the festival —and his enduring interest in No Wave.

How would you define No Wave? Art form? Anti-art form? Movement?

The upcoming event that Branden Joseph and I have organized takes it as a starting point that most of the folks interested in the subject are pretty familiar with the canonical history of No Wave via No New York, via bands adjacent to but beyond the boundaries of No New York, and via Thurston Moore and Byron Coley’s No Wave Post-Punk Underground 1979-1980 and/or Marc Masters’ No Wave.

Not to be too slippery about it, but defining or trying to articulate an essence of No Wave is not what this event is about. Instead, the impetus is more to get a sense of what has been obscured by reliance on a too-quick, too-thumbnailish of a grouping of these various activities under the heading “No Wave.” That’s why we’re excited to be showing James Nares’ films and to be talking about points of contact between music and visual art as well as between tetchy postpunk, post-Cagean new music, and dance music.

What first drew you to the No Wave scene? Why do you think it’s still compelling?

Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. DNA. Mars. I heard recordings of these groups (I was a teenager in Kentucky) just as the last of them was about to implode (DNA), and they, along with Throbbing Gristle, seemed to me to be the ones who made good on punk’s promise to flatten, to obliterate rock music. All three of those groups still sound positively glorious.

No Wave drew its considerable power from NYC’s near-total desolation. Do you think it could have happened anywhere other than New York? Could it happen now?

Year after year, it becomes a more demanding thought experiment to try to imagine Downtown as a desolate place. I mean, I suppose it can feel culturally desolate nowadays, but it’s hard to remember what it felt like for me, coming to New York in the mid-’80s to play at places like CBGBs…

How much did No Wave help explode the sanctity of the gallery space? How fundamentally did they shift established attitudes about how (and where) to make art? (This might be a better question for Branden.)

Ooh, you’re getting ahead of the game! Come to the panel discussions on November 4.

Glenn O’Brien once quipped that No Wave was a “Gong Show for geniuses.” What are some of your favorite No Wave moments —could be music, film, performance, etc.

That is such a marvelous description. What to add? Ikue Mori’s drumming. The sound-signature of Mars. The psychotic laughing jags in John Lurie’s film Men in Orbit.

***

Theoretical Music at Issue Project Room

Ut | News & Tour Dates

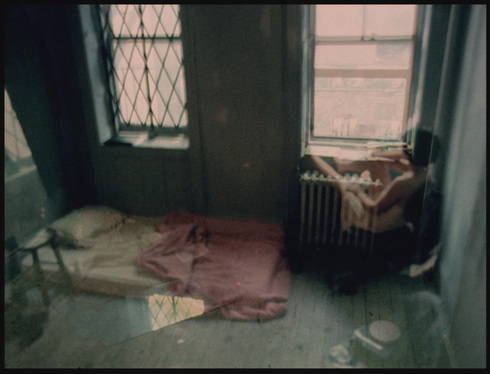

![]() Ut, “Bedouin” (Live in London, 1983)

Ut, “Bedouin” (Live in London, 1983)

PHOTO: SALLY YOUNG OF UT, 2010 | PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER SHORT