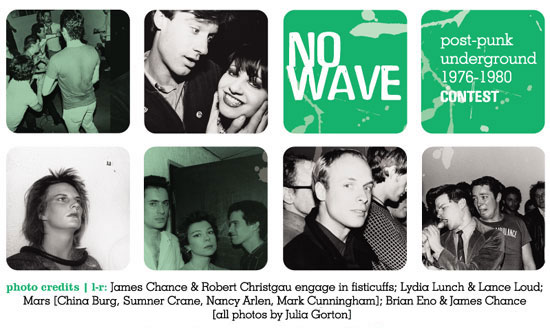

I’m pretty sure that the first mention of No Wave that I ever encountered was in an old issue of Spin(Bongo cover?) in an article written by Byron Coley. So, there’s a nice kind of symmetry to corresponding with him on the topic now. Better still, there’s a sumptuous volume to go along with, the just-released No Wave: Post-Punk. Underground. New York. 1976-1980 [Abrams], co-authored with Thurston Moore.

+ Can “No Wave” be defined?

As befits the name itself, No Wave is easier to define by what it is not than what it is. Although the earliest presumed practitioners (China/Mars) assumed they were working in a fairly orthodox “underground rock” tradition, the truth it that their sensibilities were so strange their potential to actually follow in the steps of Television (or whomever) was extremely limited.

The Smith/Verlaine/Hell generation of NY undergrounders were intoxicated by a certain kind of mystique that was based on rock & roll. Mars’ music was based on that too, of course, but it feels as though the R n’R impulse was buried under a lot of art that was deemed more functionally important than R n’R per se. The decision to start detuning guitar strings and playing slide the way that Connie did were only tangentially related to any known rock tradition.

Lydia immediately latched onto the rawness and unschooled quality of their sound, understanding that they were doing much more to break with the tradition of R n’R than any of the punk bands of that era, who were as indebted to Chuck Berry as any other generation of musicians. Punk —at the time— was supposed to be about the dissolution of technical barriers between audience and performer. People were supposed to react by thinking “Hey, I could do that.” Lydia’s huge gesture —which happened contemporaneously to things like the original Half Japanese— was to take the idea of obliterating technique literally. She denies working this theory as art, and maybe it was just pure instinct, but it created a stance inside of which musicianship became sublimated to performance, at least for the core of the bands involved. I don’t think the fact that so many bands used harsh textures in their music was so much about the need to use harsh textures as it was about the decision that it was not necessary to do otherwise. My contention that the theatrical element was as (if not more) important than musicality seems borne out by the testimony of various people that they were selected because of how they looked, or that they were enlisted for positions in bands because they were handy. People refer to certain contemporary rhythms or guitar sounds as being “no wave-y” and I know what they mean, but there’s a world of difference between, say, the keyboard sounds in Theoretical Girls and that of The Contortions (both of which were central to the whole), or the guitar sound in the Gynecologists and Teenage Jesus (ditto). What really tied them together more than anything else was having a certain attitude in a very specific time and place. Beyond that, the term is infinitely flexible.

+ What first drew you to the No Wave scene? And what makes it compelling, so many years later?

I was around Manhattan, writing for NY Rocker at the time the music was being made. I was out of town a lot, but the bands were always interesting to me, even though I didn’t necessarily like them any more than I had initially liked Suicide. But anything that extreme was compelling, and once there were records to play, it was possible to really start getting into the music in a way that was never easy for me in a live setting, except with the Contortions. It’s compelling both because it re-emerged as a hot cultural reference in the last few years, and also because many of the performers involved are still making interesting music.

+ How has the book changed in conception and/or scope since you and Thurston first kicked around the idea? What first sparked it?

The finished book is pretty much as Thurston & I imagined it. We may have initially thought about including more fliers or record covers or discographical whatsis. But we heard about the Marc Masters book. It seemed as though he’d be covering that angle pretty well, so we decided to focus on trying to get the story laid out in a fairly clear way, show how small the scene actually was, and try to sort out some of the chronological things that have long vexed serious historians of the scene. Since we were pals with many of the principals, we were able to put together a fairly coherent version. Although there are still people we’d like to talk to.

As to where the idea started, we had been talking about the need for a good no wave history since we first met back in the early ’80s. We both love Manhattan and its underground traditions, especially those of the post WWII era, and the no wave scene was such a great thing, and seemed so tractable. It was a natural.

+ No Wave drew its considerable power from NYC’s near-total desolation. Do you think it could have happened anywhere other than New York?

Well, there were parallel scenes (of sorts) in London and Berlin and Melbourne and probably other places as well. The best elements you can have for the creation of any good scene is a magnet city (the larger the better) in throes of financial hardship. There needs to be abundant cheap space available. After that, it’s all a roll of the dice.

+ At the time, was there a sense of No Wave being an anti-movement, a marked break from what had come before? Or was it a lot more organic than that?

Really, my sense of it at the time was that there were just these interesting bands, and some of them seemed to play together a lot. I’m not sure that anyone really gave much thought to any of it as a movement until the NO NY comp came out —and by the time that happened it was really all over. At the time, I was thinking of bands like the T-Girls as being “experimental,” like the LAFMS bands or something like that. New York had a certain style thing going on, but it was only after the flash had already burned our eyes that we were able to discern patterns. Not many people thought of it as a movement ’til after it was done. So I’m not sure. Branca was definitely collecting fliers by certain bands —maybe to him it was a movement.

+ I have this possibly naïve notion that everyone in DNA, Theoretical Girls, Mars, UT, etc. all lived in the same four-block radius, shared rehearsal spaces and talked art & music together, leading to a cross-pollination of musical styles and influences happening all at once. How close-knit was the scene?

There definitely were points of power in the whole thing. But it’s important to remember that things were evolving very fast at that time. Every week there was some new band with some new record that really seemed like the most important thing ever. People moved in and out bands and apartments pretty fast. But yeah, if you look at the family tree in the front of the book, you can see that things were all pretty closely linked. It really was pretty incestuous, if not always in the sexual way that some people would have you believe.

+ Was there really a strict line between the Soho and East Village factions, as Glenn Branca implies? What was the primary difference between the two?

Well, in some senses the line was porous. There were certainly people from the more established Soho/Tribeca art scene who were active in the Lower East Side bands (Donny Christensen, Sumner Crane, Nancy Arlen, etc.), but the biggest difference, in my opinion, had more to do with intent and technique. Guys like Branca and Lohn and Chatham were real musicians, in a way that the Lower East Side crowd (apart from the Contortions) were not. There were many non-musicians involved in the Lower East Side bands in a way that was not necessarily reflected on the west side. There was also the fact that Rhys had his Kitchen gig well in hand, and certain connections that flowed from that. Jeffrey Lohn had his loft and all that implies. Lydia, Arto, Mark Cunningham…these folks were not even rockers by any standard measure.

+ Reading about under-appreciated bands like Terminal, Ping Pong and Daily Life made me long for an accompanying CD. Are there any plans for such a thing? Are there bands that ended up outside the scope of the book that you wish you could have included? If so, who?

It would have been great to have a CD, but the rights would have been problematic and held the book up. It would be great project to do. And I keep hearing about people planning to do things, so hopefully it will happen. There are some bands that I wish we had more info on: Jack Ruby and Arsenal especially. But there were a few key people we had trouble tracking down, or that we could never find the right time to talk with. We transcribed over 300,000 words of interview (that was just the useful material, a fraction of the whole), but there were a lot of people we spoke with who didn’t have a lot of memories about specifics. Can’t say I blame them!

+ Was it hard to find some of these people? I’m always surprised, for instance, to see quotes from Charles Ball, given how complete his disappearance was for so many years. (Along those lines, has anyone found Ed Bahlman yet?)

There are a few people who are very elusive and have made an effort to go underground. But most of them can be found if you just ask the right people. Working at NY Rocker, I used to see Ball all the time. I just asked the people I knew he hung out with in those days and eventually found someone who’d kept in touch. I didn’t try to find Bahlman, so I don’t know. Some of these label guys are pretty squirrely.

+ No Wave was certainly the most sexually integrated scene to emerge out of punk. As Thurston says, “It didn’t pronounce itself —it just was.” In light of the fact that female musicians are, by and large, still held to so many sexist double standards, No Wave’s gender-equality is even more remarkable. Why do you think the scene was so well-balanced?

Well, the first band on the scene —Mars— was half female, but not in any kinda standard woman-rocker way. Connie was so weird, she just WAS. It was Connie who set Lydia’s brain on fire. And Lydia was the leader of Teenage Jesus pretty firmly, using a facade that was as thick as any I’ve ever seen. The Contortions (line-up 2) had Adele and Pat in roles that were instrumental rather than kittenish, then Ikue was drumming in DNA. It was just an organic way to involve people who were around. And I think it was Pat Place who said something along the lines of —most of the guys who were involved were coming from an art school background, which is not that macho to start off with. Throw a bunch of strong women into the mix, and no one will dare to say boo about it.

+ When I first heard about the book, I assumed it would culminate in an account of Noise Fest at White Columns, which happened in 1981. Why end the book in 1980?

We thought about that, but none of the bands actually survived long enough to play there (apart from DNA who were too pricey right then). It would have involved getting into the whole next generation of bands, which would be cool, but also opens a whole kettle of fish. We decided to just focus on the key bands of a brief moment, and I’m pretty happy with the way it turned out.

PS: Noise Fest needs to be released on CD. I’m just sayin’.

I agree. But Thurston stole my copy. Bastard.

No Wave: Post-Punk. Underground. New York. 1976-1980 | New York Noise, Vols. I-III | Bush Tetras [official] | Ut [official]

![]() Bush Tetras, “Too Many Creeps”

Bush Tetras, “Too Many Creeps”

![]() Jules Baptiste’s Red Decade, “Scars of Lust” (excerpt)[Live at White Columns, June 1981]

Jules Baptiste’s Red Decade, “Scars of Lust” (excerpt)[Live at White Columns, June 1981]

![]() Sonic Youth, “Untitled” [Live at White Columns, June 1981]

Sonic Youth, “Untitled” [Live at White Columns, June 1981]

![]() Ut, “Mosquito Botticelli/Sham Shack” [Live in Belgium, July 27, 1987]

Ut, “Mosquito Botticelli/Sham Shack” [Live in Belgium, July 27, 1987]