To London-based, New York City-bred pioneering power-trio Ut, No Wave meant “…breaking things down to the raw essential, ignoring rules and inventing new ones.”

Cutting out everything but the essentials began with the name: UT. Two letters, seemingly reductive but also highly evocative —it’s a primitive, declarative sound, ut. Hard T sound like cut glass. UT. Tongue to the roof of the mouth, an expelling of air — Motion. UT. Like the photo of Yves Klein’s leap into the void that graces their first proper full-length Conviction, there’s a constant taking of risks at work here. It’s not safe, this sound. Not comforting, nor narrowly circumscribed.

To listen was to constantly risk freefall, and whether or not you landed softly was immaterial.

Writer Mark Sinker once characterized Ut as a band who, at their best, “snatch[ed] grace out of disaster.” It’s a marvelously evocative phrase, because it precisely captures the knife’s-edge of tension that the band consistently and compellingly walked during their existence, which spanned a decade-plus from the first inchoate rumblings of No Wave in New York City’s then-desolate East Village through to their lengthy time as ambassadors of abstract, gritty, often beautiful NY noise in England, where they toured with like-minded iconoclasts the Fall and were signed to forward-thinking label Blast First.

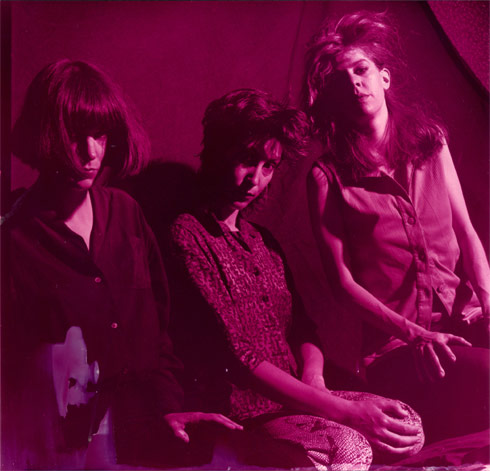

Ut —consisting of Nina Canal (Dark Day, Gynaecologists), Jacqui Ham, and Sally Young— began life in late 1978. Although founding members Sally Young and Jacqui Ham had already begun making music together, it wasn’t until a mutual friend introduced them to Nina Canal that the entity known as Ut took flight.

In the broadest sense, Ut was a democracy. Three women trading off on instruments and vocals —the set-up represented “internal democracy in a non-hierarchical structure,” to quote critic Dan Graham. They weren’t interested in having a single focal point, a Star in the spotlight, center stage. Their goals were slyer, and deeply radical: to find the beauty in chaos, the calm at the center of the storm. To wrest the purest expression out of potential anarchy. Their name may have been deceptively simple and declarative, but the music was hardly easily reduced. But then, with Ut the journey was more important than the destination. You never knew where a song might veer next —they weren’t built linearly but ran scattershot, pell-mell.

And they worked, held together with those fascinating harmonies, complex rhythmic structures that turn on a dime and powerful, irresistible bass lines that anchored everything with resolute, effortless determination. From the delicate (spirals of violin and darting harmonies on “Homebled”) to the uplifting (“Safe Burning”’s moving exhortation to “You’ve got to save yourself/For a battle that counts”) the music is full of epiphanies, small and large. As a band they were equally at home with groundswells of daunting noise as they were with quiet moments of surprising delicacy and emotional clarity. Time hasn’t dulled the intense but playful vocal harmonies —the way the voices weave around one another, the way they coo and howl and chirp. If Ut were trying to build a new musical language for themselves, they largely succeeded.

And if that sometimes made them seem a bit isolated or isolating —aloof even— it’s because they were hewing resolutely to their own path. And it seems clear from this vantage point (nearly 20 years after the release of their masterpiece In Gut’s House) that they knew precisely what they were doing. It was the rest of us who were slow in catching up, in understanding just what they were up to. Hopefully light will begin to dawn in August when Mute re-issues In Gut’s House and Griller, with the promise of more rarities to follow. (I can only hope Conviction is next in line.)

Strange coincidence first put me in touch with the band (I happen to work with Sally Young’s brother) but I couldn’t have asked for a more perfect time: Mute reissuing the Ut back catalogue, an upcoming volume of New York Noise in which they figure prominently. It’s been a busy few months for all three band members, who have suddenly found themselves in the position of revisiting the past with an eye towards presenting it to a new audience. Here’s what they had to say…

The definition of what, precisely, constitutes “No Wave” is somewhat in the eye of the beholder, thanks to the music’s genre-fluidity. But one pattern to emerge that sets the music apart from what came before is the intersection of players coming from a certain musical naïvete (or lack of training/DIY) with those who came from an academic background. Rather than there being a dividing line between the two disciplines it seems that the East Village environment encouraged not just mutual curiosity but a real cross-pollination, resulting in music that pushed boundaries (both of rock and of modern composition). Does this seem accurate to you? How would you define “No Wave”?

Jacqui: Originally there were two kinds of aesthetics going on: the sound of the so-called “No Wave” was more dirt, raw, dissonance, harder in every way, and the Soho sound was arty, intellectual, detached. This division was present even in the Talking Heads vs. Television and the Ramones, which were the East Village thing. The line was blurred, but there was a kind of reverence in Soho, in part because they were interfacing with the idea of being serious composers or they were artists coming in from that perspective.

The “No Wave” thing was more irreverent, but it wasn’t a case of academic vs. not. Only a few people were coming in from a trained perspective, but everyone was influenced by avant-garde classical composers. You heard Einstein on the Beach blaring out of windows mixing with “Lady Marmalade.” This was the environment. How much musical background people had varied, but it wasn’t necessarily influencing what they were doing, it depended on how much they were, or chose to be, indoctrinated by their past.

Nina: NYC in general has always been a creative melting pot, and THE Avant Garde city of cities, so yes, everyone was certainly influenced by those composers amongst many other influences. Some No Wavers came out of a New Music background like Rhys Chatham, Jeffrey Lohn, Jill Kroesen. There were people from literally all musical corners and many other disciplines who quickly gravitated toward this scene, which was so wide open, and either participated in a band(s) like me, Robert Appleton, Barbara Ess, or Robert Longo did (Theoretical Girls) etc. Or [else] they created their own version in other media like Rhys Chatham with Karole Armitage (i.e. Drastic Classicism).

At the time, was there a sense of No Wave being a movement of sorts, a marked break from what had come before? Or was it a lot more organic than that? I have this possibly naïve notion that everyone in DNA, Theoretical Girls, Mars, UT, etc. all lived in the same four-block radius, shared rehearsal spaces and talked art & music together, leading to a cross-pollination of musical styles and influences happening all at once. What was it really like?

Nina: NYC in late 77–1980 was in a magical zone of sorts. I had come from London after the swinging 60 & 70’s and NY actually blew my mind completely by being a place where ANYTHING was creatively possible! The scene that happened came about organically and spontaneously and burned out fast because it went against the “normal” grain of the way of things from the start. It was at once anarchic and inclusive: everyone was equal for the blink of an eye, so the field of possibilities just went wide open – BANG, just like that. And also just as suddenly there were other people of all disciplines starting up bands to play what I call “weird loud music” or spoken word stuff too, and yes, it was very village-like in many ways, with most living in the East Village or at least downtown.

Jacqui: There was a consciousness of making a new music, of progressing. You make the sounds that you need to hear —every generation does.

There was a natural progression from the Velvet Underground to Mars, as there was from 60’s rock to the Ramones. It was organic, but it was radical. It was stripping down to the essence, taking things further, taking things as far as they would go.

How did the band coalesce? What were the early shows like? Theatrical? Confrontational? Aloof? How did audiences respond to the band’s lack of a single focal point?

Sally: Jacqui and I were living in an apartment on 5th Street in 1978 and had begun writing songs together. We were going out and seeing a lot of bands and were interested in forming a band ourselves. A mutual friend of ours and Nina’s, Peter Gordon, suggested that Nina might be a good

person to play with. Jacqui knew Nina a bit and liked her and we’d seen her play with other people. We all got together in a rehearsal room in 1978 and were excited by what happened musically, so we soon became a band. Our first gig was in 1979 at Tier 3 and it was hard to tell how we went down. We had no intention of being confrontational or aloof. We were, however, trying to be theatrical in the truest sense, in terms of doing a performance that was dramatic, powerful, captivating and emotionally moving. We were just up there concentrating on making music that we felt strongly about and that made sense to us —that was our single focal point.

I don’t remember anyone at the time ever appreciating us changing instruments, and we got a lot of flak about how impractical it was. But we were very intent on making the kind of music we wanted to make, and, as I said before, that involved us not being pinned down to just one instrument or role, so other people’s disapproval didn’t prove to be much of a deterrent. However, we certainly never wanted to alienate the audience either. Personally, I would find it more dramatic and interesting to watch a band that swapped instruments, as I would be fascinated to see how each person approached each instrument differently and how the various line-ups affected the sound of the music. But that doesn’t interest people who are looking for a quick fix.

Jacqui: Sally and I had been improvising and constructing songs together and planned to do a band from high school. I met Nina in NYC. The three of us played together and it was instantaneous.

Shows were intense. That quote “snatching grace from disaster” was probably a show with a tech breakdown then the music recovered the spirit. But this also toward our aesthetic of taking things to the edge even within a musical phrase. I like the unsteady, the untamable course. We were into friction and tension is good —it is the dynamic.

What prompted the band’s move to the UK? Was it dissatisfaction with the NYC scene? Or something else entirely? How did you find Blast First?

Jacqui: We moved to England because we could gig with the Fall and make a record for free with John Loder [of London label Southern] but we had no long-range plan. At the time the scene in NYC was a ghetto, there were only 3 or 4 places to play and our record had just fallen in the ether whenCharles Ball (Lust/Unlust) went AWOL. I heard the Fall’s “Spector vs. Rector” on the radio in Nov ‘80 and was electrified. The music and the speed rap monologue with characters was on my wavelength like no other.

About a month later Ed Bahlman, who ran the 99 record shop, told me the same thing and said I should get a tape to them because they were coming to NYC in the spring. So he mid-wifed this connection and it happened that Scott Piering, an American who worked at Rough Trade at the time (and who is responsible for breaking the underground to the overground) was coming with them on tour. So I passed the tape to Scott; the Fall were into us and we ended up gigging with them until we broke up. Scott subsequently helped us a great deal and was crucial to Ut.

Sally: We were interested in what was happening in the UK music scene and the fact that a band like The Fall was thriving there intrigued us. But the idea of actually going to the UK began, on a realistic level, when John [Loder] saw Ut play in NYC and said he’d love to record an album with us. We weren’t sure if he really meant it until he came back a few months later and saw us play again and said the same thing, so we started to think he must be serious. We’d just recorded an EP for Charles Ball’s Lust/Unlust label before it collapsed, which therefore never got released. And we really wanted to get some of our music out, so it was very tempting.

Around the same time, The Fall were doing a US tour and Jacqui was determined that we should play with them. So she managed to get a tape of Ut to Mark E. Smith, who really liked it and let us know he’d definitely give us some support slots with The Fall if we came to the UK. So we had two offers that were pretty irresistible.

On top of that, Nina’s brother, who had been a film editor at the BBC for many years, had a house in London that he was in the midst of trying to sell after having just moved to LA and he said we could stay there until it was sold. So we had a chance to record, do gigs with The Fall and a place to stay —going to London suddenly seemed like the obvious thing to do.

Nina: I had also been playing guitar with Rhys Chatham, and he asked me to play “Drastic Classicism” in France for a summer festival. So I took that opportunity to take a break from NYC. While I loved [it] madly and [it] had totally changed my life forever, [it] had started to feel like a vortex, ever tighter and more intense —I had the sense that I was losing touch with the rest of the world… I went to London “for a while,” not intending to stay or leave NYC. I met with Scott Piering to discuss and cement the Fall tour, etc. and we fell in love. Jacqui and Sally soon followed and I stayed in London for the next 9 years!

Jacqui: Blast First was no accident because Paul Smith was into our NYC aesthetic. He filled a gap because no other label at that time was onto the No Wave after Charles Ball disappeared. Basically Smith was recruited to our scene by Lydia Lunch. We met him in London around the same time and knew about his plans for Blast First a few years before it actually happened. Meanwhile we released Ut records ourselves on Out Records.

TO BE CONTINUED

The songs that follow are sung by Nina Canal . “New Colour” is from the eponymous 1984 12” that also includes “Sham Shack” (which is also found on New York Noise Vol. 2); “Tell It” is from 1985’s “Confidential” 12”.

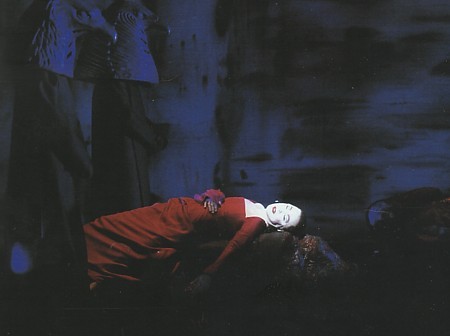

PHOTO BY SIMON VIDA