I’ve always thought of Jim Jarmusch as the original poet of slacker ennui. Stranger than Paradise(1984) set a template for a slew of mumblecore copycats who followed in that film’s wake. (And, like the Energizer bunny, they’re still going.)

And yet, Jarmusch’s vision doesn’t neatly conform to cliché: his debut, Permanent Vacation (1980), sets a ghostly tone that would echo throughout later films like Dead Man (1995), Ghost Dog (1999) and The Limits of Control (2009), all of which follow an enigmatic drifter through an increasingly chaotic world.

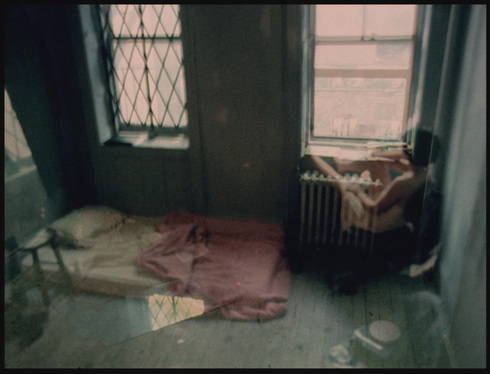

Permanent Vacation is really two films in one: a ghostly tone poem about the collapse of civilization, and a dreary day (or two) in the life of an erstwhile beatnik with romantic delusions. Although the two coexist, and occasionally intertwine, neither adds up to a cohesive narrative. For moments at a time, however, the film makes good on its nihilistic title by becoming a post-apocalyptic horror film.

Jarmusch’s themes dovetail with those of No Wave cinema, but the film is in no way confrontational. Gently and almost dreamily, it drifts along, content to let the eerie and often chilling imagery speak for itself. It’s an odd tack to take, but the restraint pays off: an unshakeable end-times vibe clings to every shot.

Jarmusch and cinematographer Tom DeCillo use long, slow pans and wide-angle establishing shots of deep shadows and looming, hollow buildings to depict a landscape ravaged by —war? Poverty? Indifference? Bureaucracy? All of the above?

Our unreliable narrator for this 70-minute tour is Aloysious Christopher Parker. Known as Allie to his friends (although it’s not clear he has any), he dresses like a hepcat, listens to bepop and mumbles like a proto-hipster.

Effectively an orphan (his father is dead and his mother, institutionalized), Parker resists social ties, preferring instead to skitter sideways through life.

He’s got a girlfriend (sort of), but treats her with blasé disdain. (In a passive-aggressive display of payback, she mutilates and defaces the copy of Maldoror that he gracelessly gives her.)

This is not, however, a film of interiors (or interiority). Allie cannot be contained, and he spends most of the film on the streets, in a kind of waking dream.

The raw, apocalypse-now vibe of the film meshes with the work of Nan Goldin, one of Jarmusch’s peers and a fellow documenter of the night owls, artsy weirdos and freaks who populated the Manhattan’s crumbling lower echelons.

Goldin made her name with The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a filmic slideshow that debuted at the Mudd Club in 1979. Goldin documented her tribe in what amounted to a family album set to music. She effortlessly captured the vulnerabilities of those (including herself) who thought themselves invincible. The initial euphoria of the scene gradually sank into hazy intoxication and then despair.

Permanent Vacation charts a similar trajectory, but Jarmusch —a Surrealist and dreamer— gives us a hopeful ending, something that Goldin’s all-too-real subjects don’t always find.

Goldin’s slide show closed with the haunting Velvet Underground song “After Hours.” In her plainspoken voice, Mo Tucker sums up the transcendent emptiness: “And if you close the door/The night could last forever/Leave the sunshine out/And say hello to never.”

![]() The Lounge Lizards, “Bob the Bob” (from Downtown 81)

The Lounge Lizards, “Bob the Bob” (from Downtown 81)

![]() The Velvet Underground, “After Hours”

The Velvet Underground, “After Hours”

STILLS FROM JARMUSCH’S PERMANENT VACATION. CINEMATOGRAPHER: TOM DICILLO