Elvis Perkins returns to his old Providence stomping grounds on December 16 for a show at the West Side’s Columbus Theatre.

This year, he released I Aubade, his first record since 2009. He also created his first film score — for February, an atmospheric horror feature directed by his brother Osgood (his sometime drummer) + due out in early 2016.

I interviewed the wry + utterly charming Mr. Perkins shortly after the release of his debut, Ash Wednesday, for the much-missed Providence Phoenix. Here’s the interview in full.

Though you don’t need to know anything about Elvis Perkins’ colorful and, at times, deeply tragic family history to appreciate his debut album, Ash Wednesday (XL/Beggars), significant details can’t help but call out to you.

The song “While You Were Sleeping” alludes to his father Anthony Perkins’s untimely death in 1992: “I made a death soup for life/For my father’s ill-widowed wife.” It’s shaded still further by the tragic death of his mother, photographer Berry Berenson, on 9/11.

And yet, Perkins’s work is neither the simple sum total of a life’s worth of incomprehensible events, nor the dour retelling of them. He’s too nimble — and too gifted — a songwriter for that. He understands all too well that elegy and celebration are two sides of the same coin.

Ash Wednesday reflects that continuum, opening with the luminous, gently loping “While You Were Sleeping,” which shifts in tone from sweetly dream-like to nearly apocalyptic; the world falls into chaos as a loved one sleeps. The unsettled mood persists, whether the songs unfold in rollicking, headlong rushes (fuzztone singalong “May Day”), stately minuets (the haunted “It’s A Sad World After All”), or hushed laments (album closer “Good Friday.”)

These accomplished songs seem to have arrived fully formed. In reality, Elvis’s musical career has been a wayward journey, its fits and starts necessitated by events both dramatic and banal. (If you were named Elvis and were raised by famous parents in the glass fishbowl known as Los Angeles, you might be self-conscious about pursuing a musical career, too.)

His efforts to escape the harsh glare of expectation led him, briefly, to Brown University where he studied, as he wryly tells me, “nothing in particular.” The school seems to have served as a developmental incubator of sorts; he began to play shows — low-key affairs — here and there. He seemed to be on his way.

When the events of 9/11 threw his plans into chaos, he kept writing, his lyrics gaining a newfound maturity. A trademark musical aesthetic began to emerge: a mix of old-world formality and conversational folksiness, of off-the-cuff charm and elegantly constructed arrangements. The overall effect is slightly out-of-time, hard to place in the musical universe — much like Perkins himself, who comes off as an owlish, slightly ascetic troubadour.

In contrast, Perkins’s live shows are upbeat and ramshackle, thanks in part to his collaborators — billed, with fanciful equanimity, as Elvis Perkins In Dearland — a ragtag group with antiquated-sounding names who play all sorts of instruments: harmonium, guitar, harmonica, upright double bass, and assorted bells and whistles. They’ve helped push Elvis’ melancholy melodicism into extroverted new territories. Expect rave-ups and waltzes, played with boisterous verve.

When I catch him on the phone — during a brief respite between road trips — he sounds weary, thanks to 15-plus months of touring. His last stable address was in North Smithfield. “Since then I haven’t been living anywhere or even receiving mail, so home is a wild, wild fantasy.”

Given his time at Brown and the sensuous care he lavishes on words, I ask him if he ever thought about becoming a writer. There is a long pause. “I’m not sure I have the attention span, but I endlessly admire those who can. It may be that I’ve admired them and myself right out of the possibility of doing it, thinking that it’s some magic that I don’t possess.”

To the contrary. His lyrics are a joy to read, shot through with bittersweet whimsy. Even at their most emotionally intense, they have a feverish, delicate quality that buoys them. Take the emotional centerpiece of the album, “Ash Wednesday,” written six months after his mother’s death. In it, the pitiless world is like a “colorized bad dream.” The chance discovery of a memento mori — “a black-and-white of the bride and groom” — sparks an immensely poignant outpouring: “No one will survive/Ash Wednesday alive/… No father, no mother/Not a lonely child.” Perkins’s warm, lilting voice transforms these chilling words into healing balm. By the time the album comes full-circle to “Good Friday” — with its tender refrain “No one will harm you/ Inside this song” — you believe him utterly.

In myth, ash symbolizes rebirth — think of the phoenix rising from its own ashes. Elvis Perkins has transformed a difficult family legacy into something cathartic. His summation? “Anyone’s family is hard to get away from. It’s a bit of a push-and-pull, wanting to articulate myself as an individual as well as being aware and proud of what my ancestors have pulled off before me.”

Before signing off, he promises to play some new songs — or, as he says with a flourish, “the future works of Elvis Perkins!” — at Saturday’s show.

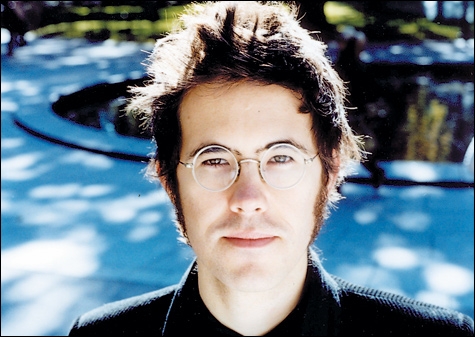

Banner photo: Elvis Perkins at Mountain Stage. Photo: Brian Blauser