I’m trying in vain to recall when I first heard the Slits. I am reasonably sure that I first heard OF them in Greil Marcus’ incredible book, “Lipstick Traces,” which weaves together iconoclastic moments in music, art, philosophy and history to create a kind of invisible history of the 20th century. (One of their first-ever recordings, “A Boring Life,” is featured on the book’s companion soundtrack, which is well worth tracking down if you can find it.)

When I DID finally hear them, I was not disappointed. In fact, the music quickly became essential to me, like air — in large part due to its fresh mix of rage, humor and incisive assessments of the way mainstream culture boxes women in.

In the proto-Internet era (and definitely pre-YouTube), I was constantly scheming to see elusive Slits footage. The day I was able to get “Typical Girls” played on the Canadian music show “The Wedge” is forever seared into my brain. And yes, the show’s host, Sook Yin Lee (a filmmaker and musician herself) made sure to play the video’s oft-truncated ending, where the group recreate the scandalous (air-quote) mud-goddess cover of their debut, “Cut.”

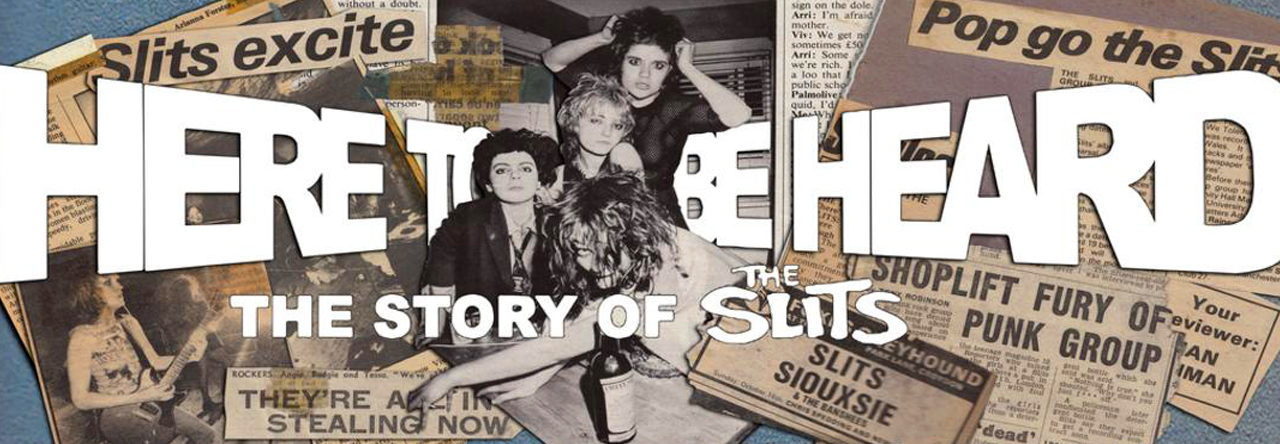

This is all a very long-winded way to say that there was no WAY I was going to miss a rare Cambridge, Mass., screening of “Here to Be Heard,” the new documentary about the Slits’ indelible existence. Rob Sheffield (“Love Is a Mixtape”) and Jenn Pelly (“The Raincoats”) are in attendance, as is original Slits drummer Paloma McLardy, AKA Palmolive, who not only helped found the band but also went on to an equally influential stint with the Raincoats.

One thing that “Here to Be Heard” establishes extraordinarily well is the visceral reactions the Slits elicited in hidebound 1970s England. While there was praise from the still-vibrant music press (albeit mixed with a great deal of backhanded comments about their lack of playing ability, which was not leveled against their punk male counterparts nearly as much), British culture as a whole recoiled from their chaotic sound and unruly visual presentation.

Greil Marcus called the Slits’ demo debut a “performance of joy and revenge, an armed playground chant.”

The fact that their name could be interpreted in multiple ways served as kind of a litmus test to weed out the inherent misogyny and condescension of the era’s — let’s face it, mostly male — critics. To take just one example: The Rolling Stone Rock Almanac wrote of their debut: “[They] will have to bear the double curse of their sex and their style, which takes the concept of enlightened amateurism to an extreme.” By contrast, Marcus called “A Boring Life” a “performance of joy and revenge, an armed playground chant.”

Joy and revenge. “Here to Be Heard” is built on a foundation of fantastic home movies, some (I assume) shot by Don Letts on the 1977 “White Riot” tour.

We see the unguarded Slits, goofing around and posing in thrift store clothes, but there’s also the darker hint of the toll that tour took on them personally — the sensationalistic press that dogged them at every tour stop; the difficulty finding hotels that would allow them to stay; the tour bus driver who wouldn’t let them on the bus; and so on. (The tour was further complicated by emotional stresses — both Palmolive and Viv Albertine had recently undergone breakups with Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, respectively.)

Once Palmolive leaves for the Raincoats, the Slits become a defacto trio with a rotating cast of musicians, including Budgie (Siouxsie & the Banshees), Bruce Smith (the Pop Group/Rip, Rig & Panic), and renowned improviser Steve Beresford (Portsmouth Sinfonia/Flying Lizards).

The sound changes too, opening up both lyrically and musically, incorporating a bass-heavy, almost jazzy, dub spaciousness and a kind of Earthbound, Gaia-centered spirituality. The band’s second album, “Return of the Giant Slits,” was released in 1981 to general puzzlement. The group split up soon after.

The film deals with this era fairly quickly, then locks into the band’s final stretch from 2005-2010, when Ari rallies the troops (some old, some new) for a Slits 2.0. Viv Albertine declined to be involved, although she gave her blessing; Ari and bassist Tessa Pollitt form the core, with Hollie Cook (singer), Dr. No (guitarist) and Anna Shulte on drums.

The rebooted group makes a splashy debut at Selfridge’s, where “Shoplifting” becomes a cheeky call-to-action. They release an album and crisscross the US. As they hurtle forward on their last exhausting tour, the normally buoyant Ari begins to show signs of uncharacteristic weariness; at other times, she lashes out at her bandmates. The band starts to unravel. Concerned, Tessa tries to talk to Ari about what’s going on, but the Slits 2.0 era ends with a whimper rather than a bang. Shortly afterwards, Ari’s mother, Nora, calls Tessa to tell her that Ari is gravely ill. On October 21, 2010, she passes away.

“The excitement and rage of the music was so intriguing.” -Rob Sheffield

It’s a somber end to the group’s beautifully unruly experiment to rewrite the rule book — not only for female musicians, but for women, period. Think of the lyrics to “Typical Girls”: “Who invented the typical girl?/Who’s bringing out the new improved model?” At their core, the Slits celebrated the unfettered joy of tearing down preconceived notions of “traditional” femininity and its trappings.

After the film, an audience member comments, “Punk was about rebellion and railing against the system. It’s so ironic that as women you had to field so much vitriol and condescension.”

Paloma agrees: “The Cape Cod Times writer summed up the Slits so well — he said we were rebelling against rebellion!” (Read Joe Burns’ piece about ‘Punk’s Palmolive’ here.)

Rob Sheffield recalls the first time he heard the band: “The excitement and rage of the music was so intriguing.” He tells an anecdote of finally scoring a Raincoats record and running to a friend’s house to listen to it and share its mysteries. A secret to be shared (and perhaps even dubbed off on a brand-new C90) with those receptive few…

Today, a new generation is discovering the potency and lacerating wit of the Slits, whose sound has never truly been imitated or bettered. What better tribute to Ari Up could there be?